Building at Google X

Disclaimer: This article outlines the technical scope of my work at Google X—describing what I built without detailing methods or results.

X, the Moonshot Factory, is where Google takes bets on world-changing tech (like Waymo’s self-driving cars). As a hardware engineer, I built novel hardware systems across wildly different moonshots—from clean-tech to consumer robotics to telecommunications. Beyond applying core technical principles as an engineering generalist, I dove into unfamiliar domains and collaborated with subject-specialists to figure out what's worth building. Below are three projects I worked on sequentially during my time at X.

Courtesy: X website

My red carpet moment at X's 'Hackademy Awards.'

Everyday Robot Project

The Everyday Robot: Courtesy: X website

The Everyday Robot Project aimed to build affordable, general-purpose robots for everyday tasks in human spaces—cleaning tables, sorting trash, disinfecting surfaces. The robot had a minimalistic form: a wheeled platform for mobility, a two-finger gripper for manipulation, and a head with cameras and lidar for perception. The goal was to build specialized hardware tailored to specific tasks rather than a humanoid form, enabling lower costs and better scalability. In 2023, the project was consolidated into Google’s DeepMind AI division, where it serves as a hardware platform for developing advanced robotics AI models.

Tactile Sensing for Grippers

For the second generation robot, the team planned to introduce tactile sensing for the grippers to expand task capabilities, and I was tasked with establishing the technical foundations for this addition.

Tactile sensing lacks established standards, so I conducted research—from commercial and academic sensors to biological systems—to define what our robot needed: touch, shear, and slip detection. I then analyzed the robot's existing sensor suite and task pipeline to derive technical specifications for these three sensing modes. I also built and integrated an experimental tactile sensor into the robot and demonstrated enhanced performance on tasks that were extremely challenging without tactile feedback—like inserting an electrical plug into a wall socket, where feeling contact and resistance is critical to success. This work created the roadmap for the team’s tactile sensing development efforts.

First generation Everyday Robot Gripper. Courtesy: NYT article

Different modalities of tactile sensing.

Project Taara

Taara Modules Deployed Courtesy: Google X Website

Taara's mission is to expand global access to high-speed internet using infrared laser beams that transmit data through open air. It's a much cheaper alternative to fiber optic cables, which currently carry most of the world's internet traffic but require expensive infrastructure—particularly challenging in remote areas and difficult terrain because the internet-carrying light beams are guided through delicate glass wires that need to be well protected . Taara’s central technical challenge is maintaining continuous, micron-level optical alignment over multi-kilometer distances under real-world environmental disturbances like wind, atmospheric turbulence, and ground vibrations. Taara's systems have been deployed in more than 13 countries and were named one of TIME's Best Inventions of 2024. The project has since spun out from X into an independent company, Taara Connect.

Laser-Steering Hardware Testing Platform

Taara’s Beam Pointing and Tracking System. Courtesy: Google X Website

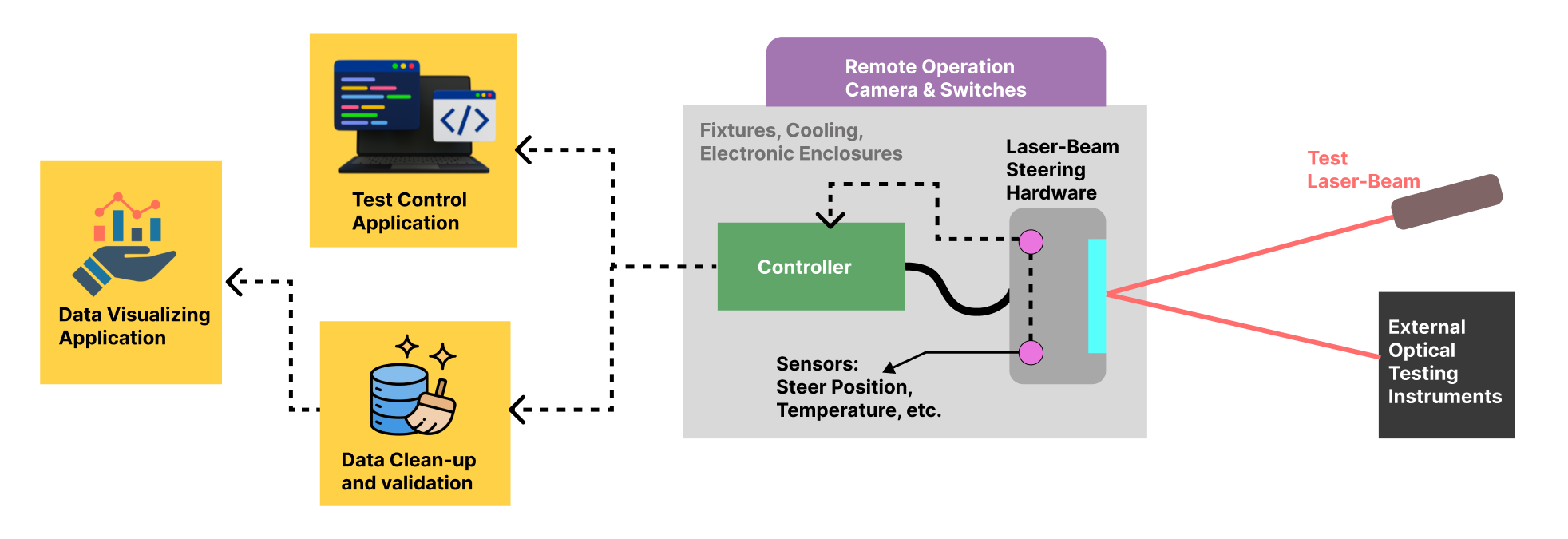

I was tasked with building a comprehensive test platform for their next-generation laser-beam steering hardware—the subsystem that keeps the laser pointed in the right direction before micron-level adjustments. The solution involved building custom software and hardware for the entire team to run various tests like response characterization, zero-drift analysis, and temperature profiling.

On the hardware side, I designed quick-swap fixtures for mounting the steering hardware on the optical test bed, enclosures and cooling systems for the electronics, and integrated a microcontroller, switches, and cameras for remote operation. On the software side, I coded a testing interface that let anyone conduct basic tests, create their own tests using simple functions, and store all the data after automatically validating, cleaning and labelling them. I also built analysis software to visualize thousands of data points collected every second over extended periods in useful graphical forms.

Laser-Steering Hardware Testing Platform

Clean-Tech Project

I worked on a project with a mission to decarbonize industrial chemical production using more efficient electrochemical reaction cells. This section focuses on the generic technical outline without any project details.

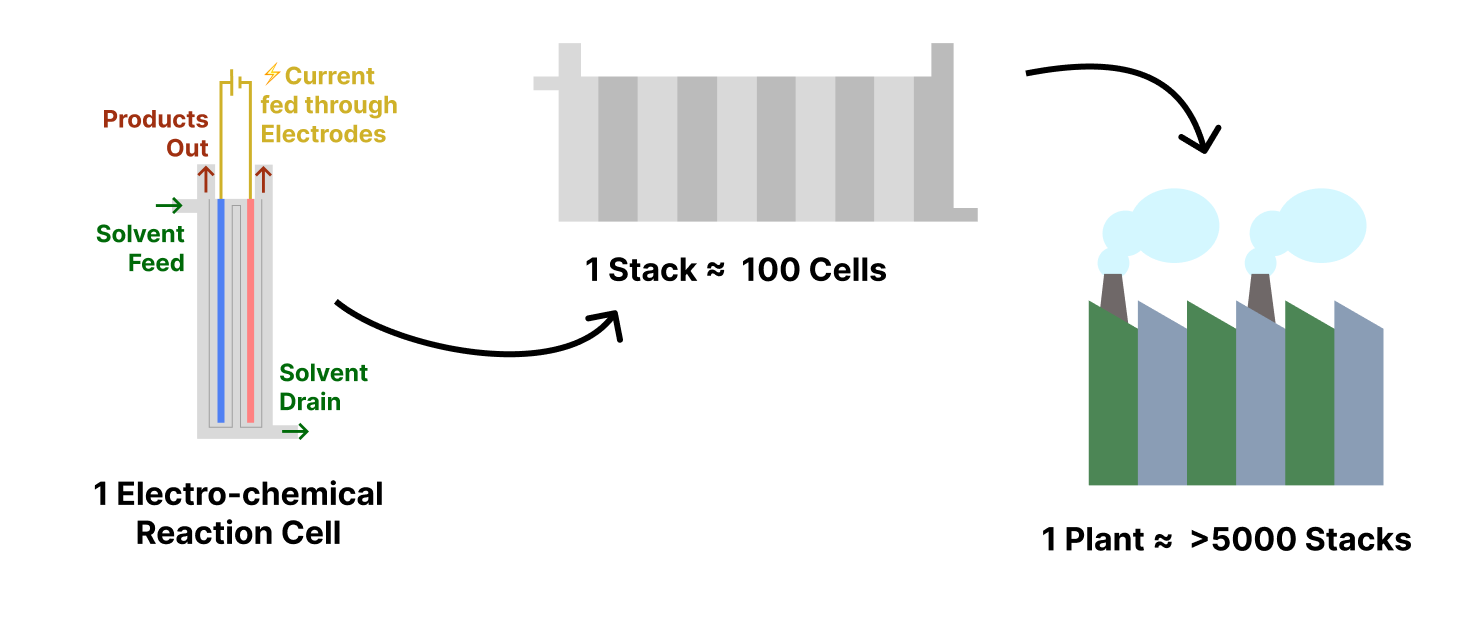

Going from one electro-chemical reaction-cell to an industrial chemical production plant

Electrochemical cells typically have an ionic solvent flowing through them—when electricity is applied, a reaction breaks down the solvent into useful chemical components. Internal channels extract these components, and the design of these channels dictates cell efficiency. By rethinking cell design from first principles, our goal was to drastically reduce plant-level setup costs, making this green alternative economically superior to traditional fossil-fuel-based methods for chemical production. The following two sub-projects were my contribution as an early-stage engineer on the team.

Real-Time Cell-Reaction Visualization

Real-Time Cell-Reaction Visualization

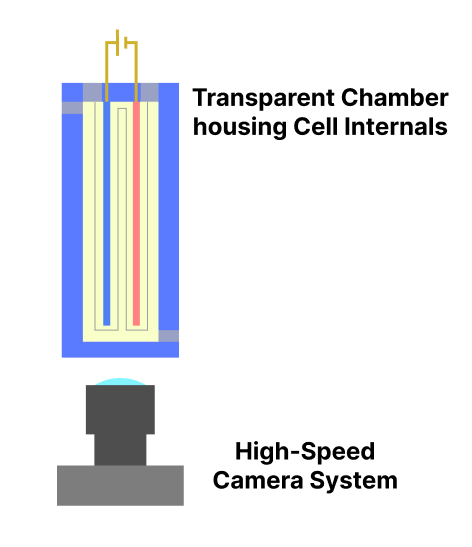

Traditional electrochemical reaction cell design evaluation relies on "black-box" data—measuring output efficiency of the cell over many hours to infer the impact of a single design-feature change. This slow iterative process provides no insight into the real-time reactions occurring inside the cell, making it difficult to understand how internal design changes affect its performance. I designed a novel method to allow the team to physically observe how internal design features in the cell influenced the reaction as they happened.

The solution involved engineering a transparent reaction chamber that houses the experimental designs of the inner cell channels and maintains a perfect seal with it, while replicating the chemical compatibility, volume, pressure, and thermal profile of a regular cell. It was paired with a high-speed camera system with precise lighting and lens calibration to capture microscopic reaction events inside the transparent chamber for analysis. This transformed the R&D cycle by moving from long-duration efficiency trials to immediate visual validation of the designs.

Life-Cycle & Performance Testbed

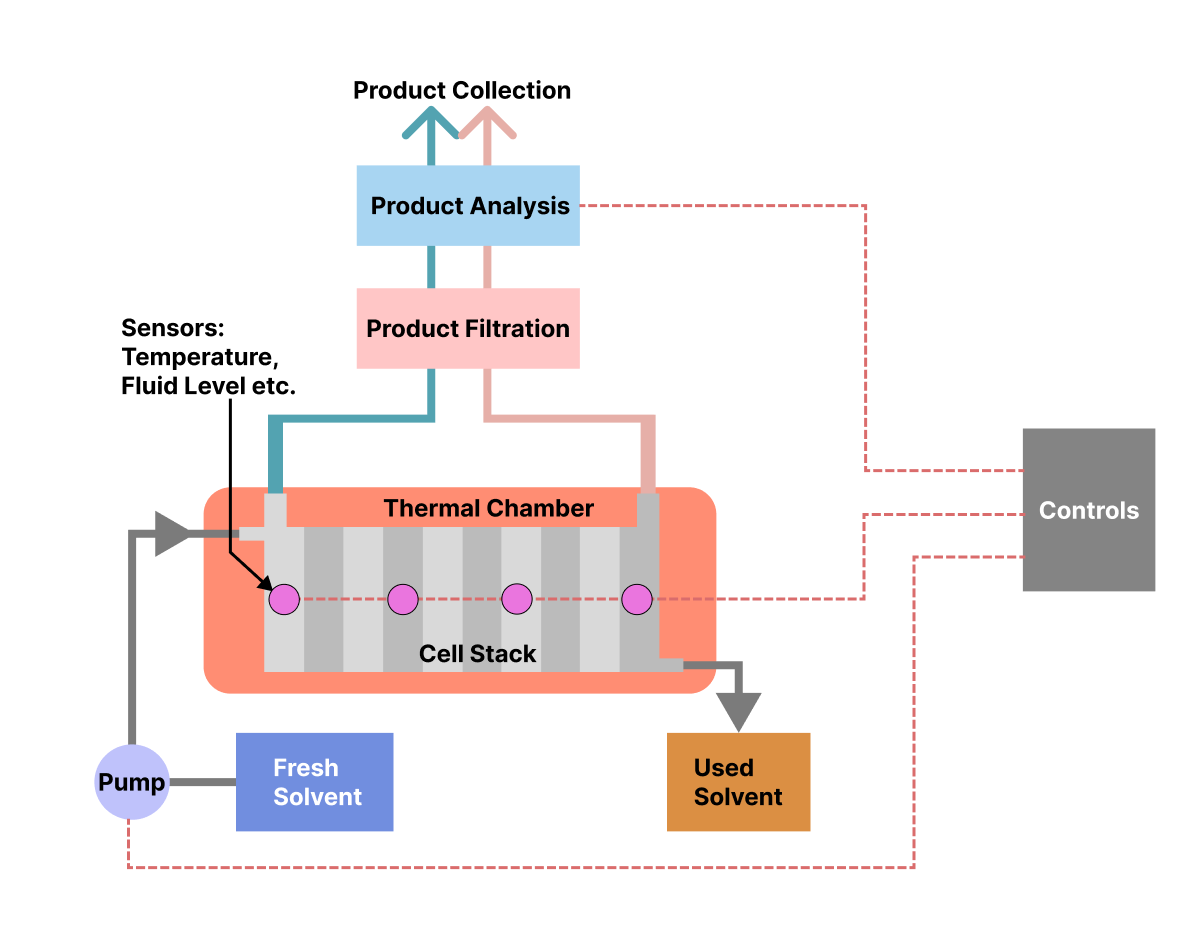

To fully validate a new electrochemical cell design, its performance must be proven at the stack level over months of continuous operation. I was tasked with designing and building a testbed that simulates the plant's environment, capable of capturing a vast array of metrics—from thermal degradation to structural deformation—that different stakeholders needed to evaluate.

Life-Cycle & Performance Testbed

I first led brainstorming sessions to synthesize requirements from all stakeholders, translating diverse data needs into a cohesive testbed system. Some requirements had no off-the-shelf solutions, so I designed bespoke equipment from the ground up: spring-loaded thermocouple fixtures for dynamic surfaces, custom level sensors for corrosive chemicals, and a thermal chamber to replicate operating conditions. I then integrated the cell-stack with all the necessary instrumentation for analysis and filtration, ensuring leak-free operation with safety interlocks for chemical and electrical hazards. After commissioning, the test stand ran for months, helping the team discover long-term insights on cell performance and degradation patterns.

The Takeaway

The word "Moonshot" is derived from JFK's speech before the Apollo Moon Missions: "We choose to go to the moon not because it is easy, but because it is hard." Working at X reinforced the fact for me that moonshots aren't about secret tools or special people—they're about breaking hard problems into testable hypotheses and attacking them systematically. The values were the same across every project I worked on, and I hope you could see it too in this article—it's curiosity to understand problems deeply, not defaulting to existing playbooks, creative thinking from first principles, rigorous testing to validate real-world practicality, and persistence through failures. I will always be grateful for this experience.

Courtesy: Google X Instagram